It had to be done. I’m usually stringent against changing themes, but I had a nagging feeling about the previous theme Rubric. Anyway, I like this one a lot, especially its column spacing, which was something I didn’t like in the other theme. But applying this also screwed up the alignment of some of the previous posts, so I had to update them as well. The simplicity here really appealed to me, and as much as I hate to change the appearance of the page, like I said, it just had to be done. Oh well.

Archive for December, 2007

Theme Change

December 29, 2007Fforde and Voltaire

December 29, 2007The Guardian has a fantastic short story “The Locked Room Mystery mystery”, by Jasper Fforde. This humorous parody of the mystery genre is well written and quite an enjoyable read. I loved the way the characters are named: Red Herring, Unshakable Alibi, Cryptic Final Message, Least Likely Suspect, Overlooked Clue, Flashback, and the detectives Detective Inspector Jack Spratt and his sidekick Detective Sergeant Mary Mary. I’d borrowed Fforde’s Lost in a Good Book sometime back but never got around to reading it, and slightly regret it now. Sigh.

I read Voltaire’s Candide last week, a satire on 18th century customs, religious beliefs and politics, while also a criticism of Leibniz’s claim that all things happen for the best and that this world is the best of all possible worlds. Voltaire criticizes Leibniz by taking his characters on an odyssey across Europe, Asia and South America, and showing us how utterly misanthropic and unjust the people of each region can be, except well, the lost land of El Dorado, which turns out to be a slice of heaven itself.

I read Voltaire’s Candide last week, a satire on 18th century customs, religious beliefs and politics, while also a criticism of Leibniz’s claim that all things happen for the best and that this world is the best of all possible worlds. Voltaire criticizes Leibniz by taking his characters on an odyssey across Europe, Asia and South America, and showing us how utterly misanthropic and unjust the people of each region can be, except well, the lost land of El Dorado, which turns out to be a slice of heaven itself.

By interposing the main story with El Dorado, Voltaire tells us that by comparison, what we see just cannot be the best of all worlds. The story moves down a depressing staircase from the instant Candide is kicked on the back and thrown out of his Westphalian palace and finally ends up at a farm in Turkey. The chapters are very brief and Voltaire never elucidates or dwells on any of the sequences, rapidly moving on to the next chapter of his tale.

Judging from the hilarious first chapter, I expected the rest of the text to follow the same tone, but rarely does Voltaire do so. Candide is more cynical than it is satirical, and Voltaire is like a mad puppeteer manipulating his characters (we see many of them surviving their death), and his readers, almost as if to prove that everything that happens has to be for the worst.

Identity Crisis

December 22, 2007 The Milgram experiment and Stanford prison study have by now become seminal standpoints from which to analyze human behavioral patterns when subjected to authority. They were both controversial and extremely successful in understanding how we as humans behave when given unconditional freedom to exert force or inflict torture on another individual or group, without even first wanting to know the victim’s crimes or any justification for the act. Just the fact that it was an order from above and the “torturers” are given full reign over the environment is enough for them to condemn the victims or make them commit ghastly and demeaning acts.

The Milgram experiment and Stanford prison study have by now become seminal standpoints from which to analyze human behavioral patterns when subjected to authority. They were both controversial and extremely successful in understanding how we as humans behave when given unconditional freedom to exert force or inflict torture on another individual or group, without even first wanting to know the victim’s crimes or any justification for the act. Just the fact that it was an order from above and the “torturers” are given full reign over the environment is enough for them to condemn the victims or make them commit ghastly and demeaning acts.

This video on Google links the Stanford study with the events of Abu Ghraib, which of course means that the Stanford experiment, was with a very high probability, successful in duplicating such real world situations; cases where the people involved don’t quite fathom the power at their hands and wield it recklessly to commit some worse-than-murder acts of violence and terror.

Another interesting aspect to the experiments is how they were a form of mind control. Give enough power to the people and make them believe, even loosely, that what they are doing is right, and they’re ready to do anything you want. Dr. Nils Bejerot later developed another psychological theory, called the Stockholm Syndrome, based on events of a robbery in Stockholm where the hostages actually defended their captors.

I guess it’s highly likely that with the right amount of pressure, even the sanest and most rational human being on Earth can be converted into a member of your terrorist gang or religious cult or anything else that you fancy. Just goes to show there’s simply no such thing as free will.

The Shop on Main Street

December 21, 2007 Jan Kadar and Elmar Klos’ influential film of the sixties is a scathing critique on the Holocaust and Aryanization that expelled Jews from their country and occupation, replacing them with the “superior” Aryans. The film carries with it a faint sense of humor that provides relief against the dramatic background of the Jew expulsion.

Jan Kadar and Elmar Klos’ influential film of the sixties is a scathing critique on the Holocaust and Aryanization that expelled Jews from their country and occupation, replacing them with the “superior” Aryans. The film carries with it a faint sense of humor that provides relief against the dramatic background of the Jew expulsion.

There’s even a fairly long (and hilarious) scene of drunken revelry that runs into the early hours of the morning, waking the cocks in the farm. Ida Kaminská is brilliant in her role of an old deaf Jew who owns the titular shop, and is unable comprehend the events happening around her, finding solace only in her cooking, listening to the gramaphone and singing praises of sons and daughters who’ve abandoned her. I read later that the film itself is notorious for not being affiliated with a particular country, Czech or Slovakia, since it was made in the days of Czechoslovakia.

Jan Kadar himself has an essay at Criterion. A couple of excerpts:

***

The most perfect reconstruction of a situation—and this brings us to The Shop on Main Street—cannot outdo a picture of fascism concentrated in the tragedy of a single human being.

…

When I thought about casting the part of Heinrich Lautmann’s widow, who runs the shop that sells ribbons, lace, buttons, I was at a loss. Czechoslovakia has no actress of the older generation with the experience of life to create such a complex, exceptional character. But Polish colleagues drew our attention to Ida Kaminská. Over 60, she is manager, producer, and leading actress at the Jewish Theater in Warsaw. She is a daughter of Esther Rachel Kaminská, the famous Polish actress who founded the theater just 100 years ago. The Kaminská family represents something of a dynasty of actors for Ida. Her husband, daughter, and son-in-law are now acting at the theater. Ida Kaminská carries the widow Lautmann’s fate within herself, and she plays from actual experience.

***

[An article regarding the film’s nationality].

The White Dove

December 19, 2007 Frantisek Vlacil’s The White Dove is an extraordinary film. Made in 1960, and part of the Czech New Wave, the film is beautifully done with frequent low angled shots lovingly looking upon the film’s characters, in particular capturing the desolation and crushed hopes of the young boy Michael (Michal) and the sullen beauty and melancholic appeal of the girl Susan.

Frantisek Vlacil’s The White Dove is an extraordinary film. Made in 1960, and part of the Czech New Wave, the film is beautifully done with frequent low angled shots lovingly looking upon the film’s characters, in particular capturing the desolation and crushed hopes of the young boy Michael (Michal) and the sullen beauty and melancholic appeal of the girl Susan.

Michal and Susan represent opposite ends of the childhood spectrum; Michal leads a constricted life, in meek submission of his failure to stand up to his friends. He is now voluntarily handicapped and refuses to climb out of the wheelchair. The cameara reveals the dark spaces around him, the black corners that shroud his apartment, the spacial depth outside the window and the narrow corridors of the building.

They together serve the purpose of identifying a kind of congestion, restraint, loneliness and helplessness in his life. The urban locality is dull and bleak, seeming to close down on him from everywhere. All this frustration is vented out by his shooting a white dove perched on top of his apartment building.

The dove belongs to Susan and has lost its way in a race. Susan represents the freedom that’s missing in Michal’s life. Surrounded by the calmness of the infinite sea, she lives an uninhibited and carefree life. Her sorrow and pain at having lost the dove is what connects her with Michal in a strange way. The dove in essence transfers her gaiety to Michal and infuses his dullness into her formerly vibrant self.

The dove belongs to Susan and has lost its way in a race. Susan represents the freedom that’s missing in Michal’s life. Surrounded by the calmness of the infinite sea, she lives an uninhibited and carefree life. Her sorrow and pain at having lost the dove is what connects her with Michal in a strange way. The dove in essence transfers her gaiety to Michal and infuses his dullness into her formerly vibrant self.

The artist and Susanne’s brother seem to play secondary roles but are equally important in the film. The artist is the one who rescues the dove and enables Michal to rediscover his childhood thus freeing him from his self-enforced captivity. His drawing of the white dove flying against a black sky and a bloodshot sun with flowers looming in the foreground is one of the many many beautiful moments in the film.

Vlacil’s handling of the camera, especially in scenes where he shoots Michal remind me of similar techniques employed by Tarkovsky when he focuses on Ivan in Ivan’s childhood. They both seem extremely similar to me: low angles slightly looking up to the face and evoking a pathos that no other film can match, and their tracking of subtle movement both on and off the frame are remarkable. This film’s scanty dialogue and brilliant use of music make it an even more indulging experience. The last shot of the dove, finally freed and flying away from the city is connected to its destination and to Susan by the sounds of the water splashing on a beach. It anticipates an untied and memorable childhood for both the protagonists (and the dove).

[An article on Frantisek Vlacil’s films].

Antoine Doinel

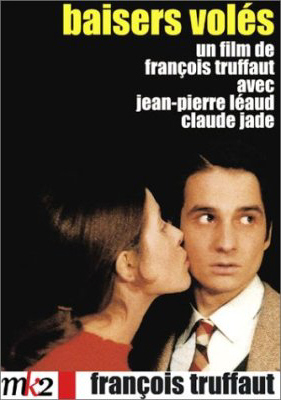

December 13, 2007 Truffaut’s alter-ego Antoine Doinel and his series of five films are unquestionably one of the standpoints of French cinema. Pierre Leaud starts off as Doinel with the brilliant (but slightly overrated) coming-of-age film The 400 Blows; then Antoine meeting Colette in Antoine et Colette; Stolen Kisses (which I consider to be the best in the series), a delectable cocktail of isolation, love, seduction and an affirmation of life; Bed and Board, with the more mature but still childish-at-heart Doinel now married to Christine with their marriage having not yet gotten past the initial “playful” phase; and finally ending with Love on the Run, a retrospective look cast in a bleak atmosphere of death and sadness, but not losing sight of the serendipitous moments, the impulsiveness and the feeling of hope that love brings.

Truffaut’s alter-ego Antoine Doinel and his series of five films are unquestionably one of the standpoints of French cinema. Pierre Leaud starts off as Doinel with the brilliant (but slightly overrated) coming-of-age film The 400 Blows; then Antoine meeting Colette in Antoine et Colette; Stolen Kisses (which I consider to be the best in the series), a delectable cocktail of isolation, love, seduction and an affirmation of life; Bed and Board, with the more mature but still childish-at-heart Doinel now married to Christine with their marriage having not yet gotten past the initial “playful” phase; and finally ending with Love on the Run, a retrospective look cast in a bleak atmosphere of death and sadness, but not losing sight of the serendipitous moments, the impulsiveness and the feeling of hope that love brings.

Truffaut’s magic with the camera and the editing board is never more explicit than in the numerous instances when he decides to follow the covert glances exchanged by Antoine and his lovers during the uncertain moments when love first decides to blossom.

It is already a well established fact that by juxtaposing love and life’s happiness with feelings of death and sorrow, but underplaying the latter, Truffaut’s films are both charming and truthful, marking love along its phases: from childhood fascination to a teenager’s pipelined view of sex to marriage’s discipline and divorce’s escape & nostagia; but also injecting lust and curiosity into the equation.

All the same, Doinel is unlike most pursuers of love. His rejection by his parents makes him seek out a family instead of only a lover. A poignant scene in Antoine et Colette is towards the end when Antoine pulls a chair to sit beside Colette’s parents after dinner and after Colette has left with another boyfriend. All the while, Colette misunderstands Antoine’s attitude thinking he’s trying to get her through her parents. It is also this parental yearning of Antoine’s that makes Love on the Run complete a full circle by tying it up with the death of Antoine’s mother who only appears in The 400 Blows.

The final film is also an introspection of Antoine’s quest for love and his egotistic attitude towards it. His conjugal tendencies clash with the passionate cravings he faces every time he meets someone new, pushing him to make mistakes while never learning from the old ones. It is then uncertain what he becomes after Love on the Run, but not unlikely that it will be a bleak future.