I wrote this in a hurry for one of my class assignments.

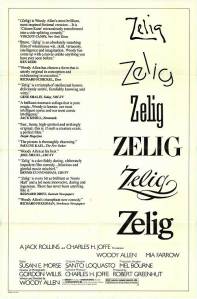

Very early in the Manhattan filmmaker’s 1983 mockumentary, Susan Sontag and Irving Howe describe an unprecedented and extremely strange event involving the eponymous Leonard Zelig. Set in Depression-era New York, we watch the antics of Zelig as he literally transmogrifies himself into the personality of his company – from rabbis to baseball players, people of oriental descent to rotund personalities, doctors to professional boxers. With each one, Zelig mingles as naturally as the chameleon camouflages into its surroundings, leading newspaper dailies to brand him with impunity, a “human chameleon” .

His discovery by the police is itself a flaccid event in the grand theme of the film, but leads to the introduction of the one person in Zelig’s world who truly cares for him: the beautiful and intelligent Dr. Eudora Fletcher (played by Mia Farrow, who decades ago played the part of the gullible mother in Polanski’s terrifying Rosemary’s Baby), a psychiatrist who does regular rounds at the local police department. His discovery by the Manhattan hospital leads to a media frenzy and subsequent exploitation of this human anomaly, giving rise to a craze in all popular cultures across America – television, radio, newspapers, dance, jazz, with people from all over the country thrilled and aroused by this strange man.

Howe, in his essay “Mass Society and post-modern fiction” describes passivity as one of the traits of mass society and opinion as having become a commodity in the market. Zelig is just such a microcosmic realization of Howe’s mass society. He is a concentrated blob of unadulterated “mass culture” teeming with derivative personalities. By borrowing the features of the crowd and to gain acceptance into the society, he discards his own identity and individuality. He is passive, always reactive and is never autonomous. He hinges on the half-developed sensibilities of others, and along with their traits, he acquires their quirks and their idiosyncrasies, while filling the void with stereotypical interpretations of his own. He has no opinion of his own, but can be quite loquacious. These “creeper vine” tendencies of Zelig to helplessly rely on others to interpret his world can be considered as a succumbent attitude, and his idea of delegating onto others the interpretation of life, progress, culture and society, is a miniaturist portrayal of Howe’s mass society.

As easy it is to criticize Zelig, he is not wrong to seek society’s acknowledgement. In fact, this was Hannah Arendt’s view on politics – that it is a social structure with little claim on economics, and politicians are essentially “attention-mongers” seeking the nod and respect of the mass. A stateless society strips the individual of his sense of identity and responsibility, belittles him, denies him the satisfaction of commitment and contribution, thus rendering him weak and powerless. Zelig’s early first-hand experience of societal abuse causes him to undergo the psychological transformation in order to please that which is hostile. But the common rational man also succumbs to the pressure of the mass society and tries to fit into his community no matter how far flung he is from it. Be it non-smokers trying to fit into a crowded bar by huffing and puffing or fashionistas trying out the latest dress craze, there is a part in all of us that wishes to please others, to put ourselves at ease and gain comfort in an environment that may be completely or partially alien to us.

Zelig is simply an exaggeration of me, of you, of all of us. Woody Allen deftly uses humor, sarcasm and biting satire to show us who we really are. Underneath the sweet smell of perfume, the layers of chiffon silk and the leather-drafted shoes, there is a soul that simply cries out to be accepted. While Zelig’s reptilist persona is rooted under psychological distress and trauma at an early age, nevertheless there is everywhere a milder version of Zelig in every one of us.

A Guardian

A Guardian  Frequently hailed as one of the greatest living filmmakers, this is Hou Hsiao Hsien’s first film outside of China/Taiwan. Hou dedicated the film to Lamorisse, whose Le ballon rouge inspired this material. At once, it is easy to spot the brilliance in his filmmaking, as the camera tracks the titular red balloon gliding across the streets of Paris, cowering behind tree-branches and deftly maneuvering the train station. The balloon is of course symbolic: here representing childhood and an age of innocence, indifference and freedom, such as that of little Simon. Simon’s mother, Suzanne (Binoche) on the other hand is a busybody, constantly occupied with work and sparing little time for her son who is tended to by a timid babysitter Song.

Frequently hailed as one of the greatest living filmmakers, this is Hou Hsiao Hsien’s first film outside of China/Taiwan. Hou dedicated the film to Lamorisse, whose Le ballon rouge inspired this material. At once, it is easy to spot the brilliance in his filmmaking, as the camera tracks the titular red balloon gliding across the streets of Paris, cowering behind tree-branches and deftly maneuvering the train station. The balloon is of course symbolic: here representing childhood and an age of innocence, indifference and freedom, such as that of little Simon. Simon’s mother, Suzanne (Binoche) on the other hand is a busybody, constantly occupied with work and sparing little time for her son who is tended to by a timid babysitter Song.